Every now and then at Screen Vistas I like to team up with Max O’Connell over at The Film Temple to tackle the work of one of our favorite directors. This time we’re looking at comedy stylist/master of whimsy Wes Anderson.

Max O’Connell: Bottle Rocket got Wes Anderson noticed in a few places, but by and large no one was really prepared for Rushmore. One of the most daring and original comedies to come out of the independent film movement, it became an instant cult classic, an example of how to make a comedy as fresh and formally exciting as any drama. It’s been over 15 years since its release, but it feels like it could have been made yesterday.

Loren Greenblatt: Remember how we had that nuanced debate about Bottle Rocket last time? That ain’t gonna happen this time, I think we both love this film beyond all reason.

MO: No. I think after a while, he’s remaking the classics of New Hollywood. He’s got Serpico, and then Heaven & Hell is him remaking a lot of Apocalypse Now.

Max O’Connell: Bottle Rocket got Wes Anderson noticed in a few places, but by and large no one was really prepared for Rushmore. One of the most daring and original comedies to come out of the independent film movement, it became an instant cult classic, an example of how to make a comedy as fresh and formally exciting as any drama. It’s been over 15 years since its release, but it feels like it could have been made yesterday.

Loren Greenblatt: Remember how we had that nuanced debate about Bottle Rocket last time? That ain’t gonna happen this time, I think we both love this film beyond all reason.

MO: Yeah. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen Rushmore. I feel almost like I can’t talk about it reasonably, it makes me so indescribably happy.

LG: It was a film I saw when I was 15 years old, the same age as the character. For a long time, it was the most important film for me. Weirdly enough, I see an uncomfortable lot of myself in Max Fischer.

MO: I think anyone who ever had any sort of precocious talent can relate to Max Fischer. But who is Max Fischer?

LG: Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman) is a teenager who’s dazzled by the possibility of life, but who gets carried away trying to grasp it and lets everything get away from him. Despite his intellect and drive he’s about to flunk out of the titular prep school to which he earned a scholarship in 1st grade (“I wrote a little one act about Watergate”). There’s a great montage early on showing how off-kilter his priorities are by showing us the clubs he’s involved with, I counted 19, set to The Creation’s “Making Time.”

MO: He’s almost uncommonly intelligent, but he doesn’t have the least bit of focus in the right places, and in a sense he sees his actual studies as beneath him. He will overcommit to the point where he’s doing great things, but he’s also failing out of class. “He’s one of the worst students we’ve got.”

LG: He does overcommit. But I also think he’s overcompensating in a way. He’s a working-class kid in a school for rich preppies, and he never got over his mother’s death. He’s hiding who he is. I think his greatest fear is being seen as ordinary in some way.

MO: He overcompensates with an almost impossible level of confidence, which does attract a lot of people, especially Dirk (Mason Gamble), his younger chapel partner and close confidant.

LG: Dirk Calloway is the fucking man.

MO: He’s the fucking man, and he’s the only one with a good head on his shoulders, as he’s one of the only one who operates out of kindness and consideration most of the time. But he attracts other people, including steel magnate Herman Blume (Bill Murray).

LG: It’s this very bizarre friendship between a 50-something man and a teenager. There’s this wonderful montage near the end where they’re riding bikes and popping wheelies, among other goofball stuff.

MO: The interesting thing about the Bill Murray character is that he’s like an older version of, well, the Bill Murray character, the guy we loved in Stripes and Ghostbusters who’s had his devil-may-care attitude worn down, and who’s deeply unhappy in spite of everything he has, or maybe because of it. He’s middle-aged, he’s deeply sad, and he sees a lot of himself in Max.

LG: I completely agree. This is a film that came in a very interesting point in Bill Murray’s career. He had a few semi-dramatic hits like Groundhog Day, but he was stuck doing the stereotypical late-period funnyman trife. He was in Space Jam two years before this.

MO: And Larger Than Life, that “Bill Murray takes an elephant cross-country” movie.

LG: It’s wacky! He was getting tired of it, and he was looking for something better. He found it in Wes Anderson, and he’s been in every Wes Anderson film since. Hell, he loved the script for Rushmore so much he offered to do it for free. This is Venkman from Ghostbusters in ten years, in the middle of a failed marriage with kids he doesn’t like. There’s a really interesting undercurrent of sadness to it, which helps make it distinctive. This is a comedy, but it’s a dark comedy.

MO: And a very melancholy one. I’d like to talk a little bit about the style of the film. You felt Bottle Rocket didn’t take place fully in Wes Anderson Land yet. Rushmore, I assume, does?

LG: Oh yeah, he got the passport status moved down to X5, to quote a different Anderson film. He had the budget he needed to do what he wanted to do visually this time. Here that style works as an extension of Max’s plays (literally, with those curtains throughout the film). It’s sort of his ultimate refuge from reality.

MO: There’s some other interesting things about the look of the film. There’s this theory I’ve had for a while, that a lot of critics we respect have echoed (including Matt Zoller Seitz, whose book The Wes Anderson Collection is essential reading). A lot of the reasons that the compositions are so orderly is that these characters are trying to keep their lives in an impossible level of control. We get to see how they can’t.

LG: I completely agree. Max is this guy who’s trying to have a ridiculous amount of control over his world, what with the clubs, and those amazing little handwritten invites that tell everyone when they should come and go. It’s his way of trying to force his control over the world he’s in. It’s hilarious what he does by sheer force of will, like trying to build an aquarium under the nose of the faculty. He has this confidence and charisma to him that makes you believe that he really could do that (Schwartzman is so good here). The dark side of that is that he’s tremendously entitled, and he has an out of control ego.

MO: He’s an arrogant little shit.

LG: He is, and every teenager is an arrogant little shit at some point, and he’s going through that phase now.

MO: Some of the things I noticed visually is a shot in the opening scene where we see how perfectly organized Max’s desk is. It’s a throwback to what Scorsese sometimes does with how characters ritualistically arrange things (think of the guns in Taxi Driver), but where Scorsese does it religiously, Max does it as a way of controlling things. It’s very charming, but it also shows how trapped he is.

LG: It’s very OCD.

MO: Another thing is how much more assured Anderson is with the editing. There’s a very simple scene between Max and his crush, the kindergarten teacher Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams). The way it cuts back and forth between the characters from the wide, deep focus shots in the anamorphic framing to much tighter shots on the character’s faces, it’s a way to show how at one point, they’re closer to each other psychologically, and at another, they’re further. An example of when they’re further, for example, is after Rosemary informs Max that a relationship between the two could never, ever happen.

LG: The library scene is wonderfully staged. There’s another transition I noticed, where, being an arrogant little shit, he tries to get revenge on Blume, who’s also fallen in love with Rosemary and started a relationship with her. His first act of revenge is burning leaves on the Rushmore school ground, and in the next scene, he sabotages Blume’s marriage by giving his wife information about the affair. And Anderson cuts from the burning leaves to a garage building that’s in smoke.

MO: There are other scenes of him getting back at Blume, too. We’ll talk about some of the other great uses of music in the film, but I love the use of Donovan’s melancholy “Jersey Thursday” in both Max’s burning the leaves and flipping the bird to Rushmore principle Dr. Guggenheim (played wonderfully by Brian Cox) and giving the information to Mrs. Blume. But even better is the montage of Max vs. Blume set to the Who’s “A Quick One While He’s Away.”

LG: Which is an especially long song, but he mostly uses one movement where the refrain is “you are forgiven!”

MO: Which, judging by what’s going on the montage, not so much.

LG: And they get pretty dark with it. It starts off with little things like Max putting bees in Blume’s hotel suite, escalates to Blume running over Max’s bike, and then gets to the point where Max cuts the brakes to Blume’s car, at which point we’ve gone off the deep end. There is something pathological about him. There were some critics at the time that wondered if Max was going to kill everyone at the end of the film.

MO: And there were some who felt the tone of that scene was misjudged. I think Ebert gave the film 2 ½ stars because he felt it didn’t know whether it wanted to be whimsical or dark. But it does show how immature these two are, and how they have no sense of proportion. And much of the movie is about them finding that balance.

LG: And I’m not going to lie, the idea that he’d go psycho crossed my mind the first time I saw it for about half a second (he does purchase a large amount of dynamite near the end). But Anderson is in control, and on repeat viewings especially, it’s clear that as dark as it is, this film is too gentle to end up that way.

MO: For all of the OCD framing, it’s a delicately handled film.

LG: I love the plays that he throws on as part of his escape from reality. He does a rehash of Serpico–

MO: It’s not a rehash of Serpico! He does Serpico!

LG: Here’s a question I have – in the film, he’s credited as the writer, not the adapter. In the world of the film is he meant to have written Serpico?

MO: No. I think after a while, he’s remaking the classics of New Hollywood. He’s got Serpico, and then Heaven & Hell is him remaking a lot of Apocalypse Now.

LG: It is every Vietnam War movie ever.

MO: The way I see it, it shows how in debt young artists are to their influences, and it’s a nice tongue-in-cheek joke about how the 90s American independent film directors were in debt to New Hollywood. For god’s sake, the year before shows Paul Thomas Anderson blending Scorsese, Altman, and Demme (among others) for Boogie Nights. You could play spot-the-reference the whole time if you wanted.

LG: And Boogie Nights hasn’t completely shaken that criticism, unfortunately. Wes Anderson isn’t completely immune to that either. Though I see more French New Wave than 70s New Wave in here. I was watching Godard’s Band of Outsiders, and there’s a lot linking that to Bottle Rocket and Rushmore, with this tenuous relationship fantasy and reality, and the handheld camerawork that isn’t talked about enough when it comes to Wes Anderson.

MO: There’s also an early classroom scene (“the hardest geometry problem in the world”) that consciously echoes a shot from The 400 Blows, too. There’s other shots taken from Lindsay Anderson’s if… (part of the 1960s British Angry Young Man New Wave), where instead of a machine-gun shootout, Max has a BB gun he uses on the bully. And there’s some American New Wave stuff. I mentioned Taxi Driver, but there are also some bits of framing that are reminiscent of Harold and Maude,

MO: Another throwback to Taxi Driver in that phone scene at Grover Cleveland, with an uncomfortable moment of things turning for the protagonist. Instead of the camera panning away as he’s rejected, we see it in all of its glory as Blume betrays him on the other line and the teacher hangs up the phone for him.

LG: He does these references, but they’re never too obvious. He reimagines them.

MO: There’s another scene that’s a direct reference to one of my favorite movies, On the Waterfront, where the sound is drowned out by a foghorn as the protagonist tells someone bad news. It’s very close, but the compositions aren’t exact. It’s him rearranging films he loves.

LG: It’s very interesting to see Anderson talk about his influences. I never hear him talking about proto-Anderson films like Harold and Maude. He said his primary visual influence on Rushmore was Rosemary’s Baby.

MO: (laughs very loudly in disbelief) Where’d you hear that?

LG: It’s in a Charlie Rose interview. The way he shoots reality slightly off-kilter influenced him.

MO: That’s incredible. There is a break between reality and fantasy in all of Anderson’s films, and this film has curtains at the beginning of every new month in the school year, almost as if we’re watching act breaks in Max’s play of his story. There’s a level of artificiality you’re either going to go for or not, and holy god, do we go for it.

LG: We’ve seen other directors try to do Wes Anderson’s thing, and it comes off as cloying or stilted. I’m thinking of Napoleon Dynamite.

MO: Or Jared Hess in general. I can also think of Little Miss Sunshine, which I don’t dislike as much as some, but which is Wes Anderson/early David O. Russell lite. Or Garden State, which I do dislike intensely. They don’t have the same warmth or self-criticism as much as Anderson, and they don’t balance whimsy and melancholy nearly as well, as you said in the last entry.

LG: And that’s something that, starting with this, he does on pretty much every film.

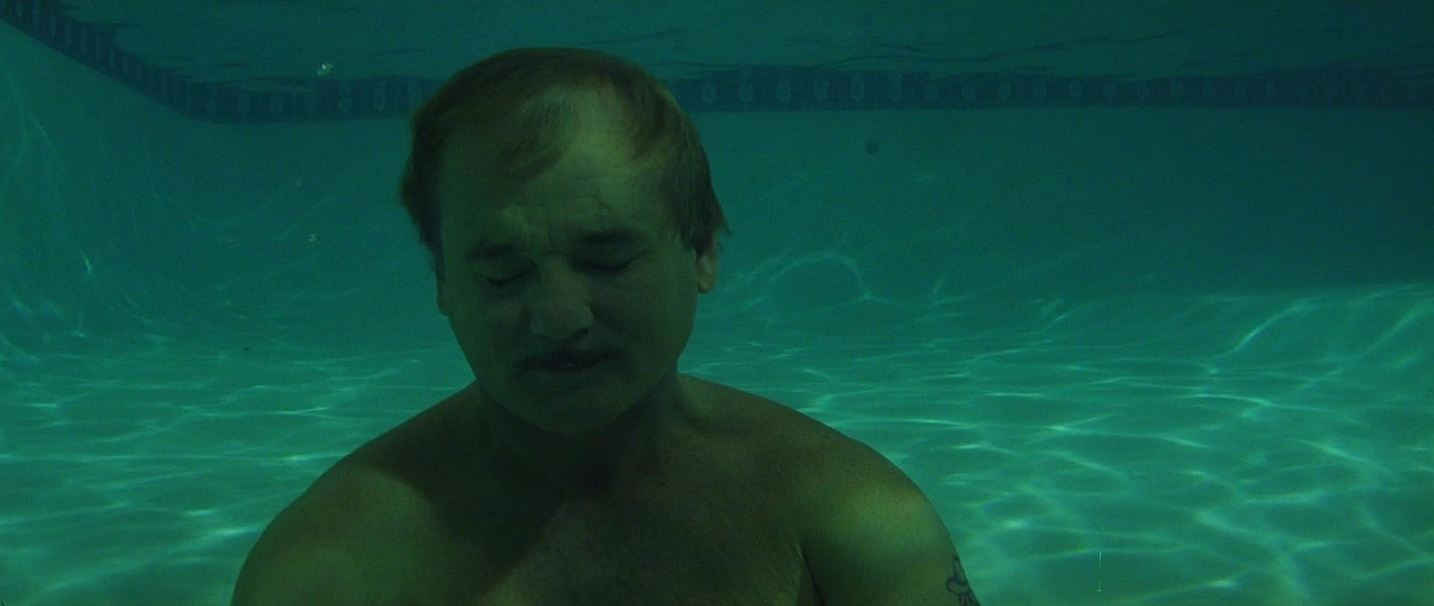

MO: Speaking of influences, there are a lot of throwbacks to Mike Nichols’s New Hollywood starter The Graduate. It’s pretty clear that Blume’s wife, even before the affair with Rosemary, is having her own affair, and Anderson described it as The Graduate as seen from Mr. Robinson’s point-of-view.

LG: Well there’s that scene at the pool party, where instead of Ben Braddock coasting in the water, we see Herman Blume sinking to the bottom of the pool. It’s a moment of great depression, and it’s a very conscious echo. We can’t really talk about Rushmore without mentioning The Graduate. There’s a very interesting way where I can see Ben Braddock as an older Max Fischer with the verve kicked out of him. And there is a similar sense of melancholy where the world is slowly breaking him. Hell, Herman Blume could be Ben Braddock twenty years later.

MO: Yeah, that great line about what happened to Ben and Elaine, “They became their parents.”

LG: Mmhmm. It’s part of what makes the friendship between Max and Blume work, they’re kind of going through a similar thing at different points in their lives. I can sort of see it in Blume’s intro, where he’s telling all of the working-class kids to take down the rich kids. There’s a bit of that rambunctiousness that he’s trying to force back into his life.

MO: There’s an intense loneliness in all three of the main characters that bands them together. Herman is losing his wife, and his kids are annoying dipshits. Max lost his mother, and he’s in a school where he’s precocious to the point where he can be off-putting, and he’s a working-class kid hiding the fact that his father (Seymour Cassel) is a barber. It’s sad, since his father is so supportive, and he relates to the “take the rich kids down” thing, but he can’t quite admit that he doesn’t come from the same stock. He wants the appearance of success at all times.

LG: That’s what I like about the bully, Magnus (Stephen McCole), a Scottish student who sees right through Max. There’s a very humanizing moment near the end where they recognize each other.

MO: Yeah. Before that, Magnus is the one person who sees that Max can be a phony and that he uses people, which Max sees as a threat (also, Magnus is kind of an asshole himself). As Max grows and starts to have more empathy for others, he sees the goodness in Magnus. They’re friends by the end!

LG: I love the way they make up. It could have been so schmaltzy, but instead Max shoots him with a BB gun, and then offers him a part in his next play. Now, we also have to talk about the third major character, Rosemary, who’s lonely in her own way. Max finds her when he reads an inscription she wrote in a book given by her old husband, Edward Appleby. She lives in his room, surrounded by his stuff. She never got over it, and Max never got over the death of his mother – he literally lives next to the cemetery where she’s buried. He cuts through it on the way to school.

MO: I feel that with Rosemary, he does fall for her, but much of it is also that he’s found someone warm and maternal as a surrogate mother. She’s so encouraging that I see it as him finding a new version of the person who supported him when he was a kid.

LG: I didn’t see that, but I see how you see it. In my mind his courtship of her is another way he’s trying to find a shortcut to adulthood by having an adult girlfriend rather than someone his own age. He does find a girl his own age by the end, Margaret Yang (Sara Tanaka), a wonderful, bright, sweet person that he treats horribly throughout most of the movie. Part of his growing up is realizing that he could act his own age and realize that he’s still a kid to some degree.

MO: And here’s the thing – he wants to grow up, but he also wants to stay in adolescence. Blume asks him what his secret is, if he’s got it so figured out. Max’s solution is “Find something you love and do it for the rest of your life. Mine’s going to Rushmore.”

LG: And when he’s expelled for the aquarium fiasco it shatters his reality, but he tries to pretend. After enrolling in public school he should theoretically drop the prep act and stop pretending to be rich, but he doubles down. He keeps wearing the Rushmore uniform like a suit of armor, and he tries to transport his Rushmore clubs to Grover Cleveland High School (he starts a fencing team, which is inexplicably not popular). But this school won’t put up with his shit as much. Rushmore at least gave him awards for Perfect Attendance and Punctuality (which, aren’t those pretty close to being the same thing?), but this school hangs up on his phone call to Blume when he doesn’t have a phone pass.

MO: I love how he gives a speech about who he is when he arrives. He’s not exactly bullied, but they look at him like he’s this weird space alien, like, “Is this guy for real?”

LG: And when he’s led out by police later after he cuts Blume’s brakes, he’s posing like a badass and it’s moving in slow motion, and girls are like, “Him?”

MO: I love that, and no one thinks he’s a badass, no one finds him nearly that charming…except for Margaret Yang, who’s equally driven, and who’s attracted to his confidence and his ambition. I also love how the first thing that really endears Margaret to Max is that we learn she faked her science project results.

LG: There’s a bit of phoniness in both of them. They’re trying too hard for things that they might be good at, but they’re not where they want to be. I get that frustration; I look back on the stuff I wrote when I was that age and it sucks! It goes to your theory that the best he can do at this point is adapt someone else’s stuff.

MO: We both admire Max a lot, but how uncomfortable is his big scene with Luke Wilson, the doctor who Rosemary brings as a date to his play?

LG: I love the arrangement of that scene. Rosemary has to reject Max, then we go to the play, Max’s retreat from reality (with the sound of applause exaggerated to an impossible degree). And then we’re brought to the dinner with Max, Blume, Rosemary and Dr. Peter Flynn (Wilson), the most affable and mild-mannered man ever. She’s getting a little cautious, and Max is upset, because he was not invited. He gets drunk because Blume made a very wise decision to buy him a whiskey-and-soda, and it goes over about as well as you’d expect. He acts like such an adult sometimes that you can understand how an adult might forget, oh yeah, he’s an immature teenager.

MO: It speaks to how precocious teenagers are treated like adults, and then they do something that shows the adults why they can’t do that.

LG: There’s some interesting foreshadowing to Anderson’s later films, like the Jacques Cousteau book that hints at The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, or the subplot about the aquarium.

MO: Do we want to talk about Anderson’s use of music? We’ve talked about his use of unexpected songs from great musicians. He doesn't use The Rolling Stones’s “Satisfaction”, he uses “I Am Waiting”, this great melancholy song that perfectly soundtracks the point where everyone in the film is lonely. Cross has left Blume, Blume is stuck in a hotel without his kids or wife, Max has essentially dropped out of school, Margaret is trying to connect to Max but can’t…there’s so many shots in this montage where characters are isolated in a side of the frame to augment their loneliness, and “I Am Waiting” is perfect for it.

LG: And later on, we get “Oh Yoko” by John Lennon for when Max and Blume rekindle their friendship and start getting back in the swing of things. No one would expect you to use those John Lennon songs, but it’s so delightful and earnest for the scene. “In the middle of a shave, I call your name”, how wonderful is that?

MO: What are some of the better lines in this movie for you?

LG: “You’re like an old clipper ship captain, you’re married to the sea.” “I know, but I’ve been out to sea for a long time.”

MO: I love the exchange when Max visits Guggeheim in the hospital after he’s had a stroke. This is the guy who was so patient with Max for so long that you can’t blame him for finally losing it, and when Max visits him out of genuine kindness, I love that he goes from being resting in a hospital to “WHADDYA WANT? IT’S FISCHER!”

LG: That scene almost doesn’t work for me, actually. It’s a good laugh, but it’s much broader than the rest of the film. I’m not complaining too much.

MO: It’s maybe a little broader, but it’s funny, so it works.

LG: The whole exchange at the end in the last scene of the film, where they explain that the Vietnam play was canceled when he tried to perform it at Rushmore. Why? “Too political?” “No, a kid got his finger blown off during rehearsals.” And the weird running gag of everyone pretending they’re getting handjobs.

MO: It’s the immaturity of the characters. It says something that Max can’t think of anything beyond that when it comes to sex. When he tries to kiss Rosemary, and Rosemary confronts him by flat-out asking what he expects with regards to sex, he’s clearly uncomfortable with it. He’s just a kid.

LG: Yeah. That’s a very hard scene to watch. It’s what separates Anderson from other comedies. He’s willing to go to dark and uncomfortable places.

MO: He never forgets that, as messed up as these people are, they’re still people. They’re worthy of dignity. The level of empathy he has for them is essential, because it’s a movie that shows growing up as learning to care about people other than yourself. Max learns to really appreciate Rosemary’s loss. He fakes being hit by a car in his last asshole act, but he realizes the profound hole her husband’s death left in her life, and how profoundly lonely Blume is.

LG: That’s an interesting scene, because it starts with him being an asshole. He’s heard that Rosemary dumped Blume, and he’s there in part to get them together again, and in part to charm her. He climbs a ladder onto her roof to get into her room and brings a mix CD with an Yves Montand song to romance her. But he realizes, “Oh, fuck, I’m a dick.”

MO: He also apologizes to Dirk and Margaret by the end, and the play, Heaven and Hell, for all of its clichés, has a remarkable effect on the characters. On one hand, the Rushmore custodian played by Kumar Pallana thinks it’s hilarious (“Best play ever, man”), but Blume who was “in the shit” during the Vietnam War, is moved by it.

LG: I love how you can tell he was there because he’s the only one who doesn’t put on the safety goggles and earplugs.

MO: The sweetness of his gestures by the end, with the dedication of the play to Rosemary’s husband along with his mother. That whole ending is sweet. He’s mended his relationship with his friends, everyone has a partner for the dance. He’s mended the relationship between Rosemary and Blume, he’s finally realized that Margaret Yang is incredible and they’re dating. There’s a friendly dance at the end between Blume and Margaret, and Rosemary and Max are left alone. There’s this great off-center framing that I think Anderson said is influenced by Demme. The shot/reverse shot shows Max and Rosemary on opposite sides of the frame, but the way it’s arranged actually shows them close together rather than far apart.

LG: I love that scene. It’s a perfect end. It’s a great teenager scene where there’s a happy ending, and he’s over her, but he’s still getting over her a little bit. But it’s going to be okay.

MO: Because he’s learned to care about other people.

LG: It’s not a trite “everything is solved” thing. It’s slightly more mature. And it’s hammered home by the use of the Faces’ “Ooh La La”, a melancholy but still upbeat retrospective on relationships.

MO: Not to mention another left-of-field song choice from Anderson, since “Ooh La La” is the one song by the Faces sung by Ron Wood rather than Rod Stewart. It’s a slightly ironic use of the song, since the lyrics are to some degree sexist, but the exuberance and the wistfulness of the song fits. And as the various couples dance in slow motion and the curtains close, we end the film smiling.

LG: I think a lot of times, great directors’ first films are a little uneven, but with Wes Anderson, he really hit a home run on the second film. This is the arrival of a major director.

MO: It’s still close to being my favorite of his, and I wouldn’t begrudge anyone who named it as their favorite.

LOREN'S GRADE: A

MAX'S GRADE: A

Roundtable Directory:

Bottle Rocket (short and feature)

Rushmore

The Royal Tenenbaums

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissiou

Hotel Chevalier / Darjeeling Limited

The Fantastic Mr. Fox

Moonrise Kingdom

Shorts and Commercials

The Grand Budapest Hotel

LOREN'S GRADE: A

MAX'S GRADE: A

Roundtable Directory:

Bottle Rocket (short and feature)

Rushmore

The Royal Tenenbaums

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissiou

Hotel Chevalier / Darjeeling Limited

The Fantastic Mr. Fox

Moonrise Kingdom

Shorts and Commercials

The Grand Budapest Hotel

No comments:

Post a Comment